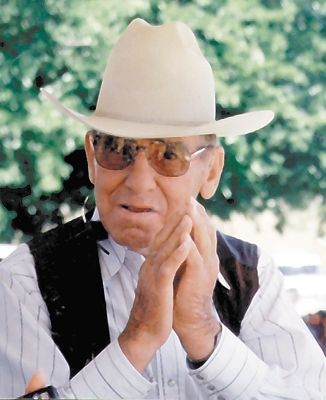

Tom Dorrance (May 11, 1910 - June 11, 2003) is perhaps the most widely revered “master horseman” and “master teacher” of our generation. Tom Dorrance is recognized by many as being the “founding father,” the original source, the place where this approach to horsemanship originated ~ an approach that has been labeled by some as “natural horsemanship,” “resistance free training” ~ on and on. However, Tom was modest about such accolades, claiming that what he knew he got from the horse. And Tom was very careful about assigning names to things. Even his hallmark book, edited by Milly Hunt Porter, doesn’t have an actual name, but rather, a phrase, “True Unity: Willing Communication Between Horse and Human.”

At the very least, Tom Dorrance has brought forward a kinder, gentler way of working with the horse; one that recognizes the horse for being exactly what it is -- a horse; one that works for cooperation, understanding -- and ultimately -- unity between horse and rider.

A number of people teach what is loosely called “natural horsemanship,” and among them there’s a continuum. On one end, information is presented as “Here’s what you do....” But moving along the continuum, closer to the source, the teaching becomes more esoteric and more ineffable. When you get to Ray Hunt, the message becomes highly intangible, and when you get to Tom’s message, there is absolutely no structure at all. It is totally non-linear. What you get, you get “organically.” It just kind of begins to soak in. All of a sudden, you realize you just learned something. You couldn’t for the life of you put it into words, but you saw something that was going on with the horse ~ that perhaps had always been going on with the horse ~ but that you had never seen before. A number of people teach what is loosely called “natural horsemanship,” and among them there’s a continuum. On one end, information is presented as “Here’s what you do....” But moving along the continuum, closer to the source, the teaching becomes more esoteric and more ineffable. When you get to Ray Hunt, the message becomes highly intangible, and when you get to Tom’s message, there is absolutely no structure at all. It is totally non-linear. What you get, you get “organically.” It just kind of begins to soak in. All of a sudden, you realize you just learned something. You couldn’t for the life of you put it into words, but you saw something that was going on with the horse ~ that perhaps had always been going on with the horse ~ but that you had never seen before.

In his book, True Unity: Willing Communication Between Horse and Human, Tom expresses his struggle with the effort of communicating what he knows and sharing it. He says, “I wish I could describe to you the picture of what I see in a horse as I look at him and watch him and try to see him as he is, A Horse. I try not to think of him as anything other than a horse....some people might think that isn’t much, but I am trying to bring out that that horse is really, really something special in his own uniqueness.”

Tom encourages the rider to arrange things so that, when the horse is going the way the rider wants him to, there’s no resistance, and no pressure. If the horse is going any other way, the rider makes it difficult; i.e., the horse runs into resistance or pressure. But -- and this is one of the big keys -- the rider, in making it difficult, makes it so that the horse comes up against his own pressure, not pressure from the rider. In other words, the rider doesn’t force or make the horse to do something; he lets the horse discover that doing that something is his best choice.

Tom explains that letting a horse come up on his own pressure is a language a horse can understand because it matches what the horse experiences in a natural setting of herd life. When horses fight to establish dominance in a herd situation, neither sets out wanting to get hurt. Each figures on the other one yielding. So the first horse applies pressure, thinking the second horse will yield. But when the second horse doesn’t yield, the first horse comes up against his own pressure that he’s applying.

Letting the horse come into his own pressure is foundational to these teachings. It’s not about punishing the horse or disciplining the horse. If a person looks at the horse and rider from the outside, he might not see the difference. But there is a big difference going on mentally inside the rider, and inside the horse! The horse is coming into his own pressure, and there he makes a choice to yield. The rider is speaking to the horse in the horse’s own language, paralleling the horse’s experiences in the horse world, and the results are that the horse has respect, and responds. Letting the horse come into his own pressure is foundational to these teachings. It’s not about punishing the horse or disciplining the horse. If a person looks at the horse and rider from the outside, he might not see the difference. But there is a big difference going on mentally inside the rider, and inside the horse! The horse is coming into his own pressure, and there he makes a choice to yield. The rider is speaking to the horse in the horse’s own language, paralleling the horse’s experiences in the horse world, and the results are that the horse has respect, and responds.

When respect is present, only a whisper of pressure is required for the horse to yield, because the horse is clear about yielding. He respects what is taking place. He’s in cooperation with it. So the bottom line is, when you get the respect, you get the response. For the rider to be effective in applying these teachings, and putting pressure on in such a way that the horse experiences it as running into his own pressure, there are certain requirements. The rider has to have an elusive quality that Tom calls feel. Also, the rider has to have timing. Feel has to come from inside the person. Tom says direction, support and encouragement may help, but there's no way to get feel from the outside.

In finding this elusive, magical dream of true unity and willing communication, the drama unfolds around one primary issue -- the horse’s need for self-preservation. In the very first chapter of his book, Tom talks about the horse’s need for self-preservation in mind, body, and spirit. It’s easy to see the need for self-preservation operating in the realm of mind and body when the horse is asked to yield and he gets afraid. But self-preservation in spirit, that’s the elusive one! Is the need for self-preservation in spirit operating when the horse is really genuinely afraid, but in spite of that fear, he still reaches for the human -- he still has the need to connect? Is the need for self-preservation in spirit his need to affirm the connection he has with the human? (And perhaps with all life?) Is the need for self-preservation in spirit what makes true unity possible between horse and rider?

In many instances throughout his book, Tom points out that the horse wants something from the human, that he’s reaching for it. And he reaches for it in spite of what his sense of self-preservation might dictate. This reaching in the midst of an opposite pull is the dynamic of who he is in relation to the human. It’s important to understand what the horse is trying to do. Tom says when a horse begins to sense that it’ll be all right to be with us, that what we’re offering is all right, we have a tremendous responsibility not to destroy that.

In 1996, I had the privilege of observing one of Tom Dorrance’s horsemanship clinics at the Merced Horseman's Association Arena in Merced, California. I was immediately struck by the ageless wisdom of this eighty-six year old man, who clearly was no respecter of time. What Tom presented seemed to have a time of its own, and its own evolution and unfoldment. Tom would tell the clinic riders, “Take all the time you need.” In the clinic setting, time disappeared, and after the clinic was over, it was months or years, and perhaps years to come, before the meaning within the meaning of what was learned would be realized. In the clinic setting, people would ask questions, and often they got Tom’s famous “It depends...” answer. Tom told the people that there’s such a variety of situations that you can’t just say, “Do this, and you’ll get that.” A person maybe would rather have had a tight little answer, all packaged up, but what Tom had to share was too full of life to be packaged. In 1996, I had the privilege of observing one of Tom Dorrance’s horsemanship clinics at the Merced Horseman's Association Arena in Merced, California. I was immediately struck by the ageless wisdom of this eighty-six year old man, who clearly was no respecter of time. What Tom presented seemed to have a time of its own, and its own evolution and unfoldment. Tom would tell the clinic riders, “Take all the time you need.” In the clinic setting, time disappeared, and after the clinic was over, it was months or years, and perhaps years to come, before the meaning within the meaning of what was learned would be realized. In the clinic setting, people would ask questions, and often they got Tom’s famous “It depends...” answer. Tom told the people that there’s such a variety of situations that you can’t just say, “Do this, and you’ll get that.” A person maybe would rather have had a tight little answer, all packaged up, but what Tom had to share was too full of life to be packaged.

The last day of the clinic, someone asked Tom if he would explain what he means in his book about the horse and spirit. Tom said he wished he could find another word due to all the stuff that people put on the word spirit, but he hadn’t been able to find one. Then, as is his usual way, Tom turned the question back to the person and asked her what it meant to her. She described a poignant moment she had had with her horse; clearly her words were inadequate to her experience but she bravely made an attempt. Tom listened, and as she talked, he held his hands out in front of him, palms facing, as if he were cradling something, something invisible, yet precious and sacred. Finally he spoke, and all he said was, “The horse comes from within. That’s what it is.”

Photography by Lynn Cox of Landmark Fine Art 805-967-7126

|